Can we learn from history? (LJ)

In the early 20th century, Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world. While Great Britain’s maritime power and its far-flung empire had propelled it to a dominant position among the world’s industrialized nations, only the United States challenged Argentina for the position of the world’s second-most powerful economy.

It was blessed with abundant agriculture, vast swaths of rich farmland laced with navigable rivers and an accessible port system. Its level of industrialization was higher than many European countries: railroads, automobiles and telephones were commonplace.

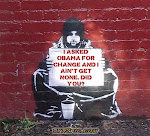

In 1916, a new president was elected. Hipólito Irigoyen had formed a party called The Radicals under the banner of “fundamental change” with an appeal to the middle class.

Among Irigoyen’s changes: mandatory pension insurance, mandatory health insurance, and support for low-income housing construction to stimulate the economy. Put simply, the state assumed economic control of a vast swath of the country’s operations and began assessing new payroll taxes to fund its efforts.

With an increasing flow of funds into these entitlement programs, the government’s payouts soon became overly generous. Before long its outlays surpassed the value of the taxpayers’ contributions. Put simply, it quickly became under-funded, much like the United States’ Social Security and Medicare programs.

The death knell for the Argentine economy, however, came with the election of Juan Perón. Perón had a fascist and corporatist upbringing; he and his charismatic wife aimed their populist rhetoric at the nation’s rich.

This targeted group “swiftly expanded to cover most of the propertied middle classes, who became an enemy to be defeated and humiliated.”

Under Perón, the size of government bureaucracies exploded through massive programs of social spending and by encouraging the growth of labor unions.

High taxes and economic mismanagement took their inevitable toll even after Perón had been driven from office. But his populist rhetoric and “contempt for economic realities” lived on. Argentina’s federal government continued to spend far beyond its means.

Hyperinflation exploded in 1989, the final stage of a process characterized by “industrial protectionism, redistribution of income based on increased wages, and growing state intervention in the economy…”

The Argentinian government’s practice of printing money to pay off its public debts had crushed the economy. Inflation hit 3000%, reminiscent of the Weimar Republic. Food riots were rampant; stores were looted; the country descended into chaos.

And by 1994, Argentina’s public pensions — the equivalent of Social Security — had imploded. The payroll tax had increased from 5% to 26%, but it wasn’t enough. In addition, Argentina had implemented a value-added tax (VAT), new income taxes, a personal tax on wealth, and additional revenues based upon the sale of public enterprises. These crushed the private sector, further damaging the economy.

A government-controlled “privatization” effort to rescue seniors’ pensions was attempted. But, by 2001, those funds had also been raided by the government, the monies replaced by Argentina’s defaulted government bonds.

By 2002, “…government fiscal irresponsibility… induced a national economic crisis as severe as America’s Great Depression.”

In 1902 Argentina was one of the world’s richest countries. Little more than a hundred years later, it is poverty-stricken, struggling to meet its debt obligations amidst a drought.

Today’s politicians, mostly Democrats, are guilty of more than stupidity; they are enslaving future generations to poverty and misery. And they will be long gone when it all implodes. They will be as cold and dead as Juan Perón when the piper must ultimately be paid.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment